THAT SINKING FEELING - A BRIEF HISTORY OF MEDIEVAL & RENAISSANCE SUBMARINES

As a writer of historical fiction I’m often asked about the plausibility of plotlines, for example my first book (The Devil’s Band which is set during the reign of Henry VIII) contains an episode involving a wooden submarine - but was the technology of the early 16th Century capable of carrying men beneath the waves? In theory the answer is yes and the boat described in the book is based on three contemporary (or near contemporary) designs.

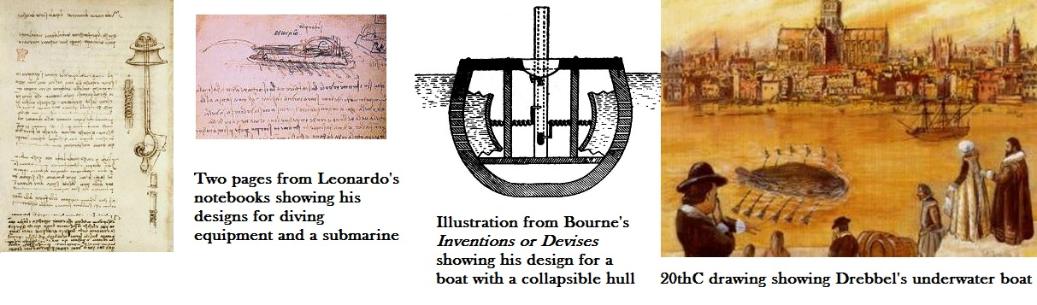

Of course, when dealing with innovative late medieval war machines, an author doesn’t need to look further than Leonardo da Vinci for inspiration. Around 1515, the great polymath designed both an underwater boat, which he called ‘a ship to sink a ship’, and a diving suit to defend Venice against attacks by Turkish galleys.

Submersion of da Vinci’s wooden boat was controlled by large leather bags attached to the hull and propulsion was by means of a hand operated crank attached to a pair of flippers at the stern. Air was supplied by means of snorkel attached to a raft, which could be disguised a floating barrel. As payment, Leonardo demanded half the ransom for any Turkish prisoners taken but he later retracted his offer, destroyed most of his notes and wrote:

"I do not describe my method of remaining underwater for as long a time as I can remain without food… this I do not publish or divulge on account of the evil nature of men who would practice assassinations at the bottom of the seas, by breaking the ships in their lowest parts and sinking them together with the crews who are in them."

Despite da Vinci’s warning, an English mathematician, gunner and sailor, named William Bourne, had no such qualms about submarine warfare. Born in obscurity in 1535, Bourne served in Elizabeth I’s navy and worked as a Gravesend innkeeper before being appointed the town’s jurat (a type of magistrate). In later life, Bourne wrote extensively on seamanship and in 1578 he published a book entitled ‘Inventions or Devises’ which contained his design for a submarine.

Like da Vinci’s vessel, Bourne’s submersible was made of wood and covered with waterproofed leather but he rejected the idea of flotation bags and flippers. Instead, Bourne proposed to propel his boat by means of oars sealed in greased leather gaskets and submersion was controlled by decreasing the boat’s overall volume. Bourne intended to achieve this by the ingenious device of building the hull with moveable walls that could be collapsed or expanded by means of a crank.

Bourne died in 1582 and, though he never had the opportunity to build his submarine, his ideas were not forgotten. In the following years, a German doctor called Magnus Pegelius, and a Dutchman called Cornelius Drebbel, both attempted to put the Englishman’s theories into practice. Sadly Pegelius’ boat, launched in 1605, became stuck in the mud of the Baltic but Drebbel had more success.

Born in Alkmaar c.1572, Drebbel first made his name as an engraver, alchemist, cartographer, engineer and grinder of lenses before moving to England at the invitation of King James I. Drebbel’s initial commission was to design the elaborate royal entertainments known as masques (which included such marvels as hydraulic organs and moving statues) but he also built optical instruments and experimented in chemistry before turning his thoughts to a working submarine.

Between 1620 and 1624 Drebbel built three vessels based on Bourne’s designs; the last of these could carry up to 16 passengers, cruise at a depth 12-15 feet (4-5 metres) and stay submerged for three hours. Crowds of astonished Londoners watched Drebbel demonstrate his boats on several occasions and the King himself accompanied the first aquanaut on one of his test dives. However, despite such royal patronage, King James’ admirals preferred to commission more orthodox vessels that operated on the surface of the water.

Failure to secure a contract with the Royal Navy meant Drebbel’s finances were not as watertight as his submarine. His profligate wife spent what little money he earned faster than he could earn it and, ironically, Drebbel was reduced to running an ale house like his predecessor Bourne. Drebbel died a pauper in 1633 and though his genius has been largely forgotten, a reconstruction of his underwater boat can be seen at Richmond-upon-Thames.

The Devil’s Band (kindle and paperback versions), featuring a pastiche of da Vinci, Bourne and Drebbel’s submarines, is available via Amazon. To order click here